Audience: non-U.S. founders and investors who formed a U.S. LLC with 2+ owners (default tax status = partnership) and want to stay compliant—even if you have little/no U.S. tax knowledge.

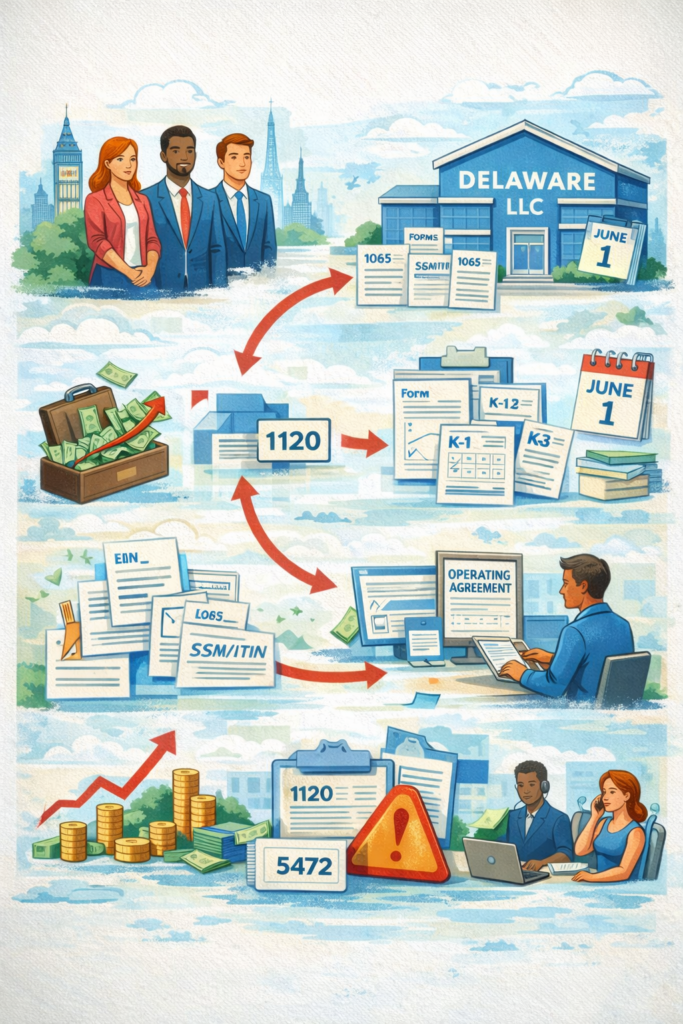

Common fact pattern this covers: a Delaware LLC, foreign members (Europe, etc.), early-stage funding, software/SaaS, mostly (or only) non-U.S. customers, and questions like “Do we owe U.S. tax?” and “What forms do we file?”

Table of contents

- 1. What is my U.S. LLC for tax purposes?

- 2. What must a foreign-owned multi-member LLC file each year?

- 3. When is Form 1065 due, and how do extensions work?

- 4. Do we owe U.S. tax if we have no U.S. customers?

- 5. What are K-1, K-2, and K-3—and do we have to do them?

- 6. Is investment money “taxable income”?

- 7. Are mentors/VC really “members” if we promised equity later?

- 8. Delaware compliance: annual tax and deadlines

- 9. Related: What if we switch to a single-member LLC? (5472 risk)

- 10. Related: Nonresident investing/trading and U.S. tax

1) What is my U.S. LLC for U.S. tax purposes?

If your LLC has two or more members, the IRS generally treats it as a partnership by default (unless you file an election to be taxed as a corporation).

In practical terms:

- The LLC files a partnership return.

- The LLC issues tax forms to each member showing their share of results.

- Whether you personally owe U.S. tax depends on U.S. source and U.S. trade/business rules (covered below).

2) What must a foreign-owned multi-member LLC file each year?

At minimum, most multi-member LLCs taxed as partnerships file:

- Form 1065 (U.S. Return of Partnership Income)

- Schedule K-1 for each member (your “partner report”)

- Potentially Schedules K-2 and K-3 (international reporting), depending on facts and requests (see Section 5)

3) When is Form 1065 due, and how do extensions work?

For partnerships, Form 1065 is generally due the 15th day of the 3rd month after the tax year ends (for calendar-year partnerships, this is March 15). You can request an extension using Form 7004.

Even if your business is “small,” “pre-revenue,” or “just raised funds,” filing deadlines still apply.

4) Do we owe U.S. tax if we have no U.S. customers?

Not necessarily. Many foreign-run startups with:

- no U.S. office,

- no U.S. employees/contractors acting as dependent agents,

- and work performed outside the U.S.

…can have U.S. filing obligations (Form 1065/K-1s), but little or no U.S. income tax—especially if revenue is foreign-source and not effectively connected to a U.S. trade or business.

But be careful: the answer can change fast if you add any of the following:

- U.S. employees or founders working in the U.S.

- a U.S. office / coworking space used as a real business location

- U.S. dependent agents closing deals or routinely contracting on your behalf

- U.S. customers + U.S. performance of services (implementation, onboarding, support) from inside the U.S.

Rule of thumb: “U.S. entity” does not automatically mean “U.S. tax due,” but U.S. presence often changes the result.

5) What are K-1, K-2, and K-3—and do we have to do them?

Schedule K-1 (almost always)

Your partnership issues a K-1 to each member showing their share of income/loss/credits.

Schedules K-2 / K-3 (international reporting)

K-2/K-3 are used when partners need international tax information (foreign taxes, foreign activity, etc.). The IRS has created exceptions and “request-based” rules in some situations, including a small partnership filing exception and rules keyed to whether a partner requests K-3 information by a certain date.

If you have foreign members, you should assume K-2/K-3 may be relevant until a qualified review confirms an exception applies.

6) Is owner investment “taxable income” to the LLC?

Usually, no—true owner capital contributions generally aren’t “revenue.”

But you must classify it correctly in your bookkeeping because mislabeling funding as “sales” can:

- distort your tax return,

- distort each partner’s capital account,

- and create compliance problems later.

Best practice: track funding separately (capital contributions vs. loans vs. revenue), and maintain a clean balance sheet.

7) Are mentors/VC really “members” if we promised equity later?

This is one of the most common (and risky) startup misunderstandings.

If they are already members:

If you legally gave them an ownership interest now, then they are partners now, and you likely must:

- include them in partnership ownership records,

- issue them K-1s,

- consider whether the ownership grant had tax consequences.

If they are not yet members:

If you only promised future equity (e.g., vesting upon success, sale, or milestones), they may not be members yet—depending on how the deal is documented (profits interests, options, side letters, etc.).

Why this matters: partnership tax reporting is driven by who is a partner and when, not by informal understandings. If your documents and cap table don’t match reality, you can end up with incorrect K-1s and messy corrections later.

Practical advice: get your operating agreement, cap table, and “promise-to-issue equity” documents reviewed together so the tax filing matches the legal reality.

8) Delaware compliance: annual tax and deadlines

Delaware LLCs generally have:

- a $300 annual tax, and

- it is due June 1 (and Delaware LLCs typically do not file an annual report).

This is separate from your IRS filing requirements.

9) Related: What if we switch to a single-member LLC later? (5472 risk)

If your U.S. LLC becomes single-member and foreign-owned (disregarded entity), a different compliance regime often applies—most notably Form 5472 reporting (with a pro-forma return structure in many cases).

This is high-stakes because the penalty for failing to file Form 5472 can be $25,000, with additional penalties possible if the failure continues after notice.

10) Related: Nonresident investing/trading and U.S. tax

Foreign founders often ask: “If I trade stocks/crypto/futures via a U.S. broker, do I owe U.S. tax?”

A key baseline rule in the Code imposes 30% tax on certain U.S.-source “fixed or determinable” income (like certain passive income) received by nonresident aliens, unless reduced by treaty or an exception applies.

There are also special rules (including a 183-day presence rule for certain gains) that can change outcomes if you spend significant time in the U.S.

Bottom line: investment activity can be “simple” for some nonresidents, but it becomes complicated quickly depending on presence, source, and the type of income.

If you want this reviewed quickly and correctly (entity classification, member list, K-2/K-3 exposure, and a clean filing plan), book a consultation here:

https://oandgaccounting.com/appointment-booking-form/