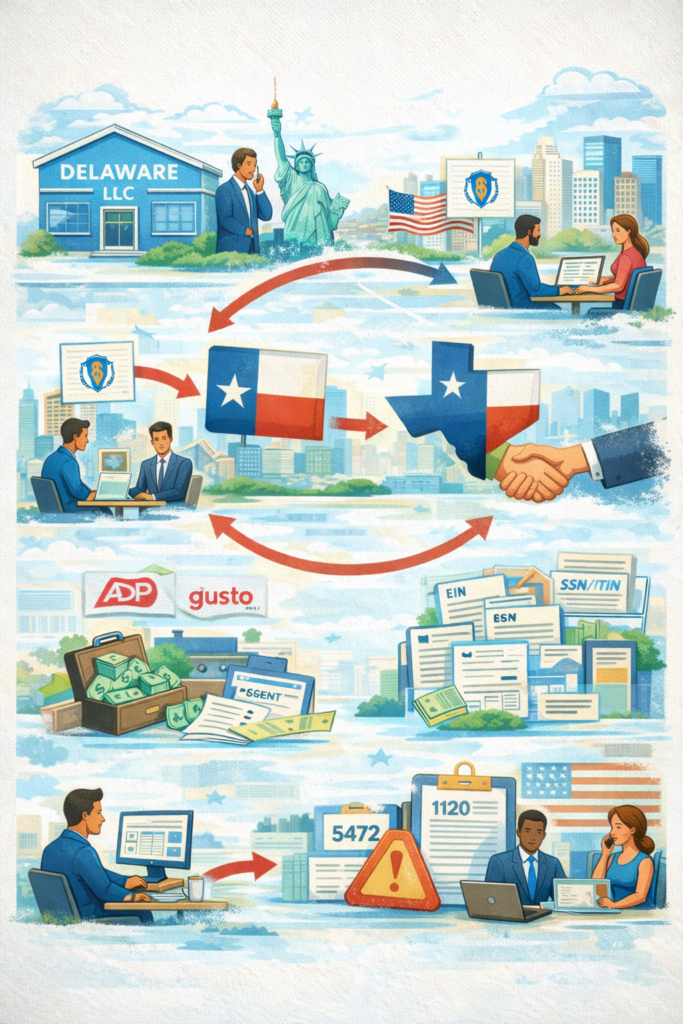

A practical tax + compliance FAQ for international founders (U.S LLC → In-State operations)

If you’re a non-U.S. founder who formed a U.S LLC “just in case,” and you’re now landing your first U.S. client (or relocating a team member to the U.S.), your compliance profile changes fast. The biggest mistakes happen when companies treat “U.S. operations” like they’re still doing purely foreign business.

This FAQ breaks down the most common questions for foreign-owned startups that:

- are formed as a U.S LLC,

- now have a U.S. client and/or a U.S.-based employee/contractor, and

- want to stay compliant without overpaying taxes or triggering avoidable filings.

1) We formed a Delaware LLC, but we didn’t “do anything” in the U.S. yet. Do we still have filing obligations?

Yes, often.

A Delaware LLC can create U.S. filing obligations even when the founders are foreign and customers are non-U.S. The exact forms depend on how the LLC is classified for U.S. tax purposes:

- Multi-member LLC (partnership by default) → typically files Form 1065 (plus Schedules K-1, and often K-2/K-3).

- Single-member LLC owned by a foreign person/entity (disregarded) → typically files pro-forma Form 1120 + Form 5472 (information reporting).

- LLC electing to be taxed as a corporation → files Form 1120 as a U.S. corporation.

The mistake many foreign founders make is assuming “no U.S. tax = no U.S. filing.” Filing and tax are not the same thing.

2) Our LLC is multi-member. What is the due date and what happens if we miss it?

For a partnership (multi-member LLC), the federal return is generally due March 15 (for calendar-year entities).

If you’re not ready, you typically file an extension by March 15, which pushes the due date to September 15.

But the extension must be filed on time.

Filing late can trigger penalties even if there is little/no tax due. Partnership compliance is deadline-driven.

3) We’re foreign founders and our customers were non-U.S. until now. Why does getting a U.S. client matter?

Because once you have U.S. customers and/or people physically working in the U.S., you start dealing with concepts like:

- Effectively Connected Income (ECI)

- U.S. trade or business exposure</li>

- State tax and payroll rules

- Foreign qualification requirements

In plain English: the U.S. starts seeing your business as “operating here,” not just “selling from abroad.”

4) We now have an employee relocating to Massachusetts for a U.S. project. What’s the first compliance step?

Foreign qualification (state registration).

If your company is formed in Delaware but has an employee physically working in other states, For example states like Massachusetts will typically view the company as “doing business in MA”.

Foreign qualification is essentially:

“An out of state company, registered to legally operate in Massachusetts.”

Why it matters:

- It helps protect your ability to enforce contracts in that state.

- It reduces legal problems if your company is sued or needs to sue.

- It’s often required once you have ongoing presence (employee, office, etc.).

Bottom line: If you have boots on the ground, treat the state presence seriously.

5) Do we need foreign qualification if the employee is remote and working from Ireland for a Texas client?

Usually no—not just because the client is in Texas, but because the worker is not physically present there.

State compliance is heavily influenced by physical presence (employees, offices, job sites).

A remote foreign worker serving U.S. clients from abroad is very different from having someone in-state.

6) What payroll registrations do we need once we have a U.S. employee?

You typically need state payroll accounts (varies by state), including:

- State withholding tax account

- State unemployment insurance account

- Other state-specific employer registrations (if applicable)

Payroll providers like ADP/Gusto often help set up these accounts, but you must ensure it’s completed correctly.

Important: Payroll compliance is not optional. Once wages are paid in the U.S., withholding and reporting requirements apply.

7) Our U.S. LLC will start receiving U.S. client payments. How should we handle bookkeeping?

Your U.S. entity must keep its own books:

You should maintain a clean system that tracks:

- client invoices and payments

- payroll and payroll taxes

- reimbursements and project expenses

- intercompany transfers (if the foreign parent funds the U.S. entity)

Software is fine (Xero, QuickBooks, etc.), but the books must reflect what actually happened and keep transactions properly categorized.

8) We need to “pre-fund” the U.S. LLC from Ireland before the U.S. client pays. Do we need to declare the transfer?

Not in the way most founders fear.

Generally, you wire the funds and record it correctly in the books as one of the following:

Option A: Capital contribution

Simpler. You record the funds as an owner/parent contribution.

Option B: Intercompany loan

More formal. Requires documentation (loan agreement, interest terms, repayment schedule).

Practical rule: If you want simplicity, use capital contribution unless you have a strong reason to create debt.

9) We want a holding company to own the U.S. LLC instead of individual founders. Do we need to file anything with Delaware?

Often Delaware does not require public ownership updates for an LLC the way people assume.

But you must update internal documents such as:

- the Operating Agreement

- membership/ownership schedules

- internal resolutions/consents

However: tax classification consequences can change dramatically when ownership changes (especially if the LLC goes from partnership to single-member).

10) If the LLC becomes foreign-owned single-member, does the foreign parent need to file U.S. returns?

It can, yes—this is where many founders get surprised.

If the U.S. LLC becomes a foreign-owned single-member disregarded entity, the LLC itself generally files information reporting (e.g., Form 5472 with a pro-forma 1120), but the foreign parent may become the filing/tax “taxpayer” depending on activities and the existence of a U.S. trade or business.

Many foreign founders prefer to avoid pulling the foreign parent into U.S. filing obligations, especially corporate U.S. returns like Form 1120-F, which can be complex and expensive.

11) Can we elect the U.S. LLC to be taxed as a corporation to simplify parent-company exposure?

Yes—often using an entity classification election.

Why founders choose this route:

- The U.S. entity becomes the taxpayer.

- The foreign parent becomes a shareholder, not the filer.

- U.S. reporting and tax stay “contained” in the U.S.

This can reduce complexity, but you must plan for cross-border payment structure (dividends vs service/management fees, transfer pricing logic, documentation, etc.).

12) If the U.S. LLC is taxed as a corporation, do dividends trigger U.S. withholding tax?

Often yes. Dividends paid from a U.S. corporation to a foreign shareholder are commonly subject to withholding (frequently 30% unless reduced by treaty).

That’s why many companies structure cross-border cash movement through:

- service fees / management fees (must be real, documented, and priced reasonably), or

- other legitimate intercompany charges (case-by-case).

This is not a “hack.” It must be supportable and compliant.

13) Our EIN “Responsible Party” is someone who left the company. What do we do?

File Form 8822-B to update the Responsible Party with the IRS.

This is important for:

- IRS correspondence

- account control

- future compliance

You also update the Partnership Representative on the partnership return going forward (for multi-member LLCs taxed as partnerships).

14) Do we need a registered agent in both Delaware and Massachusetts?

Yes.

- Delaware registered agent → required because your LLC is formed there

- Massachusetts registered agent → required once you foreign qualify there

Registered agent services are common and relatively inexpensive, but you must keep them active.

15) What are the most common mistakes foreign founders make once they enter the U.S. market?

- Not foreign qualifying in the state where staff is physically working

- Running U.S. payroll without proper accounts set up

- Mixing U.S. and non-U.S. operations in a way that makes income sourcing confusing

- Making ownership changes without understanding tax classification consequences

- Assuming “no tax due” means “no filing required”

- Paying the foreign parent without proper documentation or logic (fees/dividends)

If you want a clean plan tailored to your facts (entity structure, U.S. employee state, U.S. customer contracts, and parent-company exposure), book a strategy call here: Schedule a consultation: https://oandgaccounting.com/appointment-booking-form/