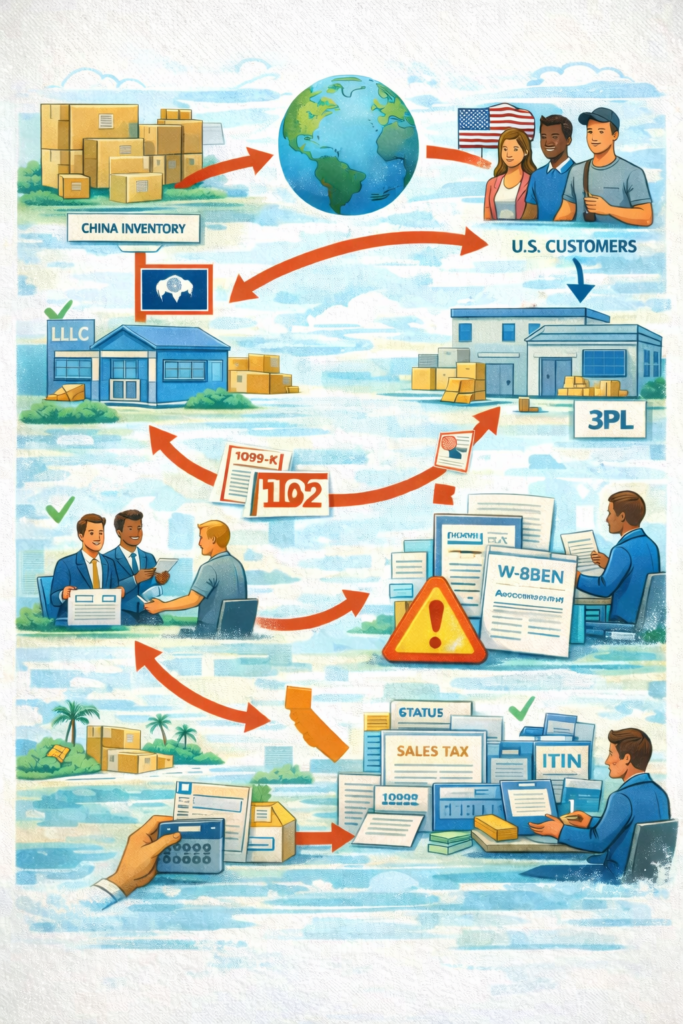

This FAQ is written for the common setup where you:

- are a nonresident alien (not a U.S. tax resident),

- own a U.S. single-member LLC (often Wyoming/Florida/Delaware),

- sell physical products to U.S. customers (Shopify/Stripe/etc.),

- keep inventory in China (or other non-U.S. locations),

- may use a U.S. 3PL/fulfillment center (similar to FBA),

- have no U.S. office and no U.S. employees,

- hire independent contractors (Upwork/Fiverr/UGC creators),

- and want to avoid accidentally creating a U.S. trade or business (USTB) or filing the wrong U.S. tax forms.

Big picture: Federal income tax rules (USTB/ECI), treaty rules (Permanent Establishment), federal information returns (Form 5472), and state sales tax rules are different systems. You can be “fine” for one and still have obligations in another.

1) What does “U.S. trade or business” mean in plain English?

You’re generally in USTB when you have regular, continuous, profit-motivated business activity in the U.S. through:

- people (employees or dependent agents),

- a place (office/fixed location),

- or meaningful operational functions carried out in the U.S. that drive your revenue.

For foreign founders, the practical question is usually:

Do I have U.S. people or a U.S. footprint that looks like “operations,” not just “customers”?

2) If I have 100% U.S. customers but operate from abroad, does that alone create USTB?

Usually, no. Having U.S. customers (even all U.S. customers) does not automatically create USTB.

What changes the analysis is typically:

- U.S. employees, or

- a dependent agent in the U.S. who can act in your name (especially contract/signing authority), or

- you performing revenue-generating activity from within the U.S. in a structured way.

3) Does using a U.S. 3PL/fulfillment center automatically create USTB?

Often no, but it depends on the relationship and control.

Why many 3PL arrangements are lower risk for USTB

- serve thousands of merchants,

- operate under their own procedures,

- and are paid as a service vendor (you don’t “direct” their workforce day-to-day).

In that classic model, the 3PL is more like a service provider than your U.S. staff.

When a 3PL can start looking risky

- the 3PL is economically dependent on you (effectively exclusive),

- you have meaningful control over personnel/process beyond normal vendor instructions,

- the 3PL (or someone you hire locally) handles returns, refurbishing, customer service, or other core activities in the U.S.,

- or you have U.S. people managing logistics/operations on your behalf.

Practical rule: A 3PL that is truly independent and non-exclusive is usually treated very differently than a U.S. employee or a dependent agent.

4) What’s the difference between a “dependent agent” and an “independent agent”?

Think of it like this:

Independent agent (lower risk)

- has many clients,

- runs their own business,

- you can’t dictate how/when they work,

- they don’t “stand in your shoes.”

Dependent agent (higher risk)

- effectively works for you like an employee,

- you control them,

- they can negotiate/close/sign contracts for you,

- they carry out core business functions in the U.S. in a way that looks like your U.S. operation.

A typical 3PL is usually closer to independent agent behavior.

5) If I hire a full-time person in the U.S., is that always a problem?

If they perform core business functions, it’s often a problem for USTB/ECI and treaty PE analysis.

Higher-risk activities for a U.S.-based worker

- supplier negotiations / sourcing / procurement,

- product research that drives what you sell,

- managing logistics or returns,

- customer service tied to revenue,

- contract negotiation or signing.

Lower-risk (often “support”/administrative) activities

- bookkeeping,

- mail scanning,

- basic admin tasks that don’t materially drive sales decisions.

But: Even “admin” workers can create payroll and state registration requirements. The key point here is: core revenue-driving work in the U.S. is where USTB risk climbs fast.

6) I use Fiverr/Upwork contractors—does that protect me?

Using platforms like Fiverr/Upwork often helps show:

- the contractor is in an established marketplace,

- they’re available to many clients,

- your relationship is project-based, not employment.

But platform use is not magic. A contractor can drift into “dependent agent” territory if:

- they become near-exclusive to you,

- you control their schedule and methods,

- they act with authority on your behalf (especially contracts),

- they become “your U.S. team in practice.”

7) I want to pay U.S. UGC creators/actors for ads. How do I reduce risk?

This is usually manageable if you keep it truly project-based.

Best practices:

- Use a clear independent contractor agreement (deliverables, scope, no control over hours).

- Pay per deliverable/project (not salary-style).

- Avoid making them your “always-on” U.S. marketing department.

- Don’t give them authority to negotiate or bind your business.

- Make sure your real-life behavior matches the contract.

Important: Paper helps, but substance wins. A perfect contract won’t save a relationship that behaves like employment.

8) I’ve heard “inventory in the U.S. automatically creates USTB.” Is that true?

Not automatically—but it’s a major fact that can shift the analysis depending on how sales and fulfillment are structured.

Key variables:

- Do you own inventory stored in the U.S.?

- Where does title pass (important for sourcing rules in resale structures)?

- Are U.S. functions limited to storage + shipment by an independent 3PL, or do you have people doing more?

Bottom line: Inventory + 3PL is not automatically fatal, but it’s exactly the kind of setup where many foreign founders choose to file a protective return to reduce risk.

9) If I’m in Germany (treaty country) vs. the UAE (non-treaty), what changes?

If you truly have no USTB

Treaty or no treaty, you often don’t need the treaty analysis at all.

If the IRS argues you do have USTB

- A treaty country may allow you to argue no Permanent Establishment (PE).

- A non-treaty country doesn’t give you that treaty “backstop,” so risk management often leans more on domestic law + protective filings.

10) What is a “protective return” and why do foreign founders file one?

A protective return is a procedure-driven filing used to:

- put the IRS on notice that you exist,

- explain why you believe you’re not taxable (no USTB/ECI or no PE),

- and preserve your right to deductions if the IRS later challenges your position.

For foreign e-commerce founders, protective filings are often used as a risk-control tool, especially when:

- payments flow through U.S. processors (1099-K),

- operations involve U.S. fulfillment,

- or you’re moving to a non-treaty jurisdiction.

The exact form depends on your structure (foreign individual vs foreign corporation, disregarded entity vs corporate election). The protective filing must be done correctly, with the right disclosures.

11) “Can I file a return with zeros even though I have U.S. customers?”

A protective filing is not the same as hiding income or filing false returns.

A proper protective approach is disclosure-based: it includes statements explaining:

- what you do,

- where functions occur,

- why your income isn’t ECI / why treaty relief applies (if relevant),

- and why your filing is protective.

If you knowingly file something misleading (e.g., “zero activity” when you’re running a real business), that’s not protective—it’s inaccurate.

12) I get a 1099-K from Stripe/Shopify. Does that mean I owe U.S. income tax?

Not automatically.

A 1099-K is an information match item. It can raise questions if your reporting is inconsistent, but it doesn’t determine the final tax outcome by itself.

Real risk: mismatches, wrong tax classification on file with processors, and not having a clean compliance position if the IRS asks.

13) People “just mark W-9” even though they’re not U.S. persons. What should I do?

That’s exactly the kind of thing that can cause:

- withholding/account shutdown issues,

- penalties for false statements,

- audit complications,

- and downstream legal exposure.

Correct approach: document your foreign status properly (typically via the appropriate W-8 form) and structure compliance so your processor/tax profile matches reality.

14) Do I need an ITIN for sales tax permits and compliance tools?

Usually you don’t need an ITIN to be legally required to register for sales tax. Many states will accept an EIN (or allow paper registration without SSN/ITIN).

But practically:

- Some state portals are unfriendly without SSN/ITIN,

- Paper processing is slower,

- Vendors sometimes push ITIN because it simplifies their workflow.

How foreign founders commonly obtain an ITIN

ITINs are generally obtained by filing Form W-7 with a qualifying tax filing or qualifying exception. The correct path depends on your facts and whether a protective filing is appropriate.

15) Do I need to issue 1099s or collect W-8s?

This depends on what your U.S. LLC is doing and who it’s paying.

General guidance:

- If your U.S. LLC is paying U.S. contractors outside of payment processors, 1099-NEC obligations may apply (based on how the payments are made and the facts).

- If you pay foreign contractors, collecting the appropriate W-8 form is often how you document their foreign status.

This is an area where many foreign-owned LLCs accidentally step on rakes because they focus only on “income tax” and forget the information reporting side.

If you’re a foreign founder selling to U.S. customers and you want a clear answer on USTB risk, 3PL exposure, protective filings, and ITIN strategy, book a compliance review call here:

Schedule your call: https://oandgaccounting.com/appointment-booking-form/